Laura Codruța Kövesi held the post of the Prosecutor General of Romania from 2006 to 2012. Between 2013 and 2018 she served as the Chief Prosecutor of the National Anti-corruption Directorate. During her term in office, the Directorate significantly increased its effectiveness in detecting corruption offences, including among high-ranking politicians or judges and prosecutors. In July 2016, Ms Kövesi was appointed for another three-year term as Chief Prosecutor.

Her position was weakened after the parliamentary elections in December 2016. On 22 February 2018, Romanian Minister of Justice held a press conference during which he presented a report containing a negative assessment of Ms Kövesi’s work. It draws attention to her criticism of the government and accuses her of abusing power, interfering with ongoing investigations and falsifying evidence. The Minister also said that he had requested the dismissal of Laura Kövesi.

Legally, the decision was to be made by the President of Romania after consulting the Consiliul Superior al Magistraturii (“CSM”), the Romanian judiciary council overseeing judges and prosecutors. The CSM gave a negative opinion on the proposal to dismiss Ms Kövesi, which served as a basis for the President’s refusal to issue a decree removing her from office. However, the Minister of Justice decided that the President did not have the power to refuse the Minister’s request and therefore submitted a motion to the Constitutional Court to resolve the jurisdictional dispute. The Constitutional Court ruled that the President could not refuse to grant the Minister’s request and was obliged to dismiss Ms Kövesi. The President complied with the judgment and issued a decree dismissing Laura Kövesi from her post.

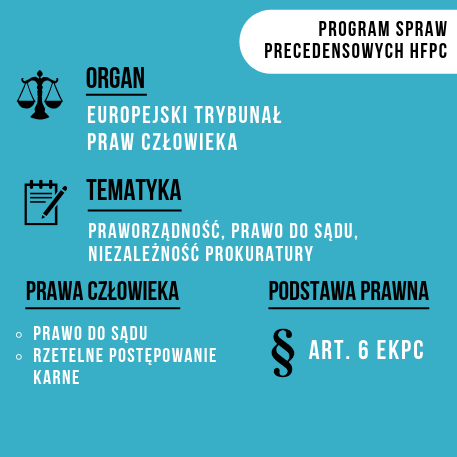

She lodged an application with the ECtHR, accusing Romanian authorities of an infringement of ECHR Article 6 (right to a court), 10 (freedom of expression) and 13 (right to an effective remedy). Kövesi also argues that she had not had the opportunity to challenge the presidential decree or actively participate in the proceedings before the Constitutional Court. In her opinion, her dismissal was a consequence of her criticism of the legislative activities of the government, which she was entitled to express as the prosecutor general.

HFHR intervenes and submits amicus curiae brief

The HFHR pointed out that the case of Ms Kövesi should be interpreted in light of the standards of independence of the prosecution service and its importance for the protection of human rights. It was emphasised that an efficient and independent prosecution service is one of the cornerstones of a national human rights system. A politicised prosecution service will not be able to carry out its tasks objectively, especially in cases where certain human rights violations are attributable to politicians from the ruling camp. It can also be used to initiate politically motivated criminal proceedings.

According to the Foundation, the existence of an independent judiciary does not, by itself, eliminate all threats resulting from the politicisation of the prosecutorial arm of the state. The accused person can be very much harmed by the mere fact that criminal proceedings are launched against them. In addition, courts exercise only an ex-post review of certain acts of the prosecutor that strongly interfere with the rights of individuals.

The guarantees of prosecutors’ independence are relatively rarely established in national constitutions or binding international treaties. However, relevant recommendations are often made in soft-law instruments. Key guarantees of independence include, inter alia, a fair system of appointments and promotions, adequate conditions of employment, measures against arbitrary dismissals, the proper formulation of disciplinary rules and ensuring that prosecutors have the right to a court in cases concerning their employment. International standards also underline the importance of respecting the freedom of expression of prosecutors, in particular in matters related to respect for the rule of law.

The HFHR also pointed out that the independence of prosecutors had been severely restricted as a result of the 2016 overhaul of the prosecution service in Poland. This “reform” included the merging of the posts of the Prosecutor General and the Minister of Justice, while granting the former far-reaching powers to interfere in individual investigations. The independence of prosecutors is also limited by factual measures such as initiating disciplinary proceedings and interorganisational transfers. In the opinion of the Foundation, restrictions placed on the independence of prosecutors may have a negative impact on the effectiveness of proceedings conducted in cases of suspected violations of the law by government officials. A perfect example of this risk is the course of criminal proceedings launched to investigate the Polish Prime Minister’s failure to publish judgements of the Constitutional Tribunal.